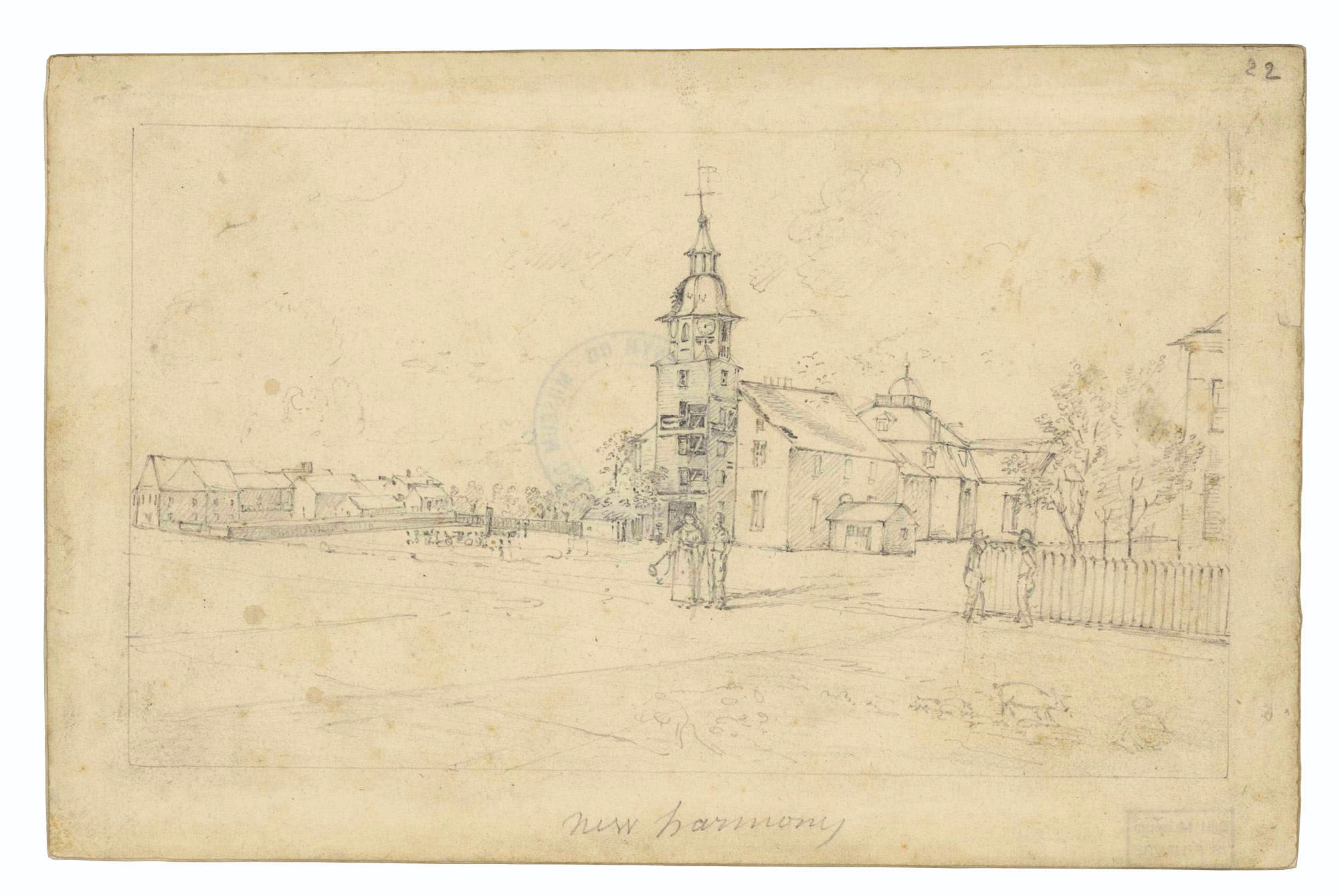

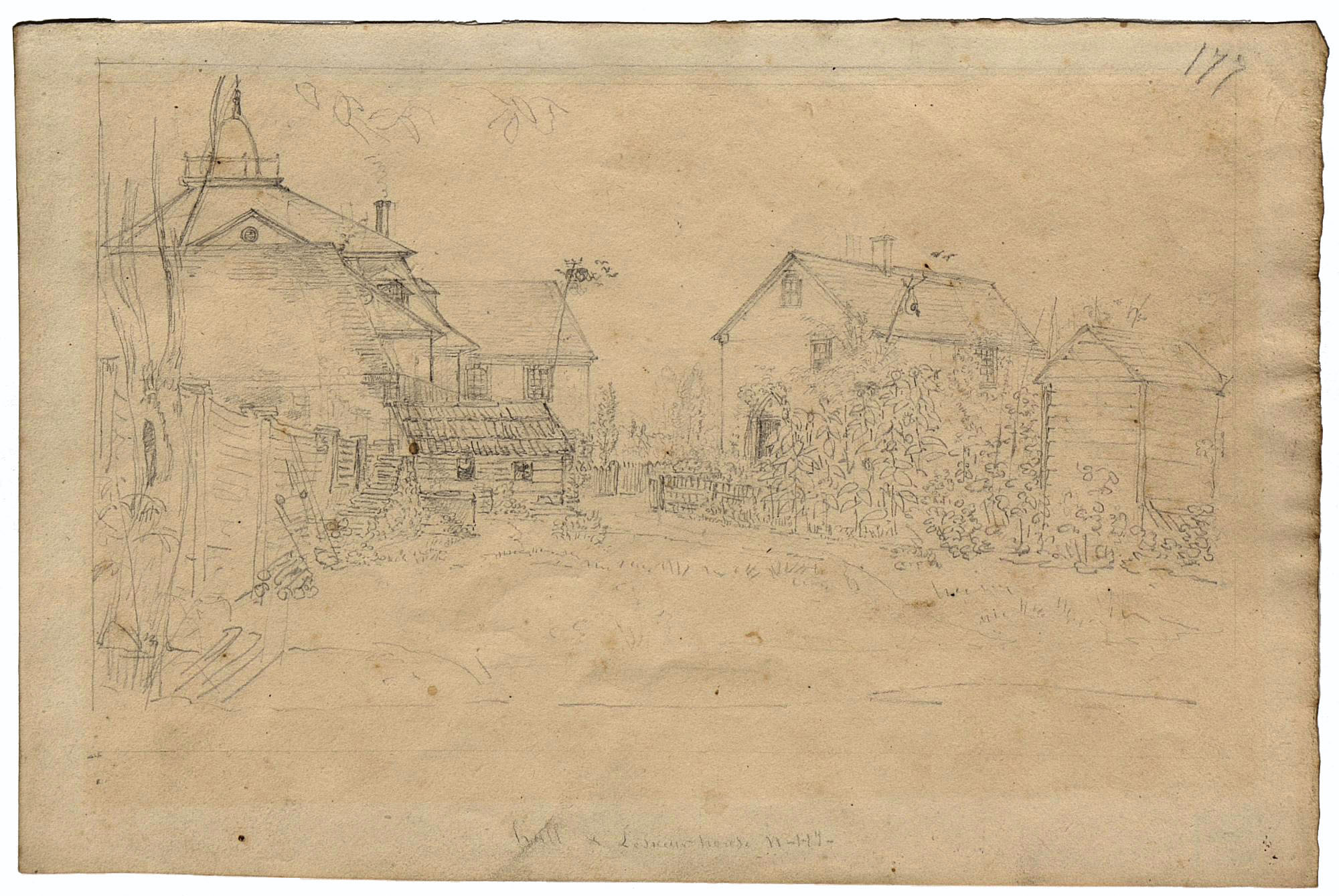

Utopia at the Frontier:

New Harmony, Indiana

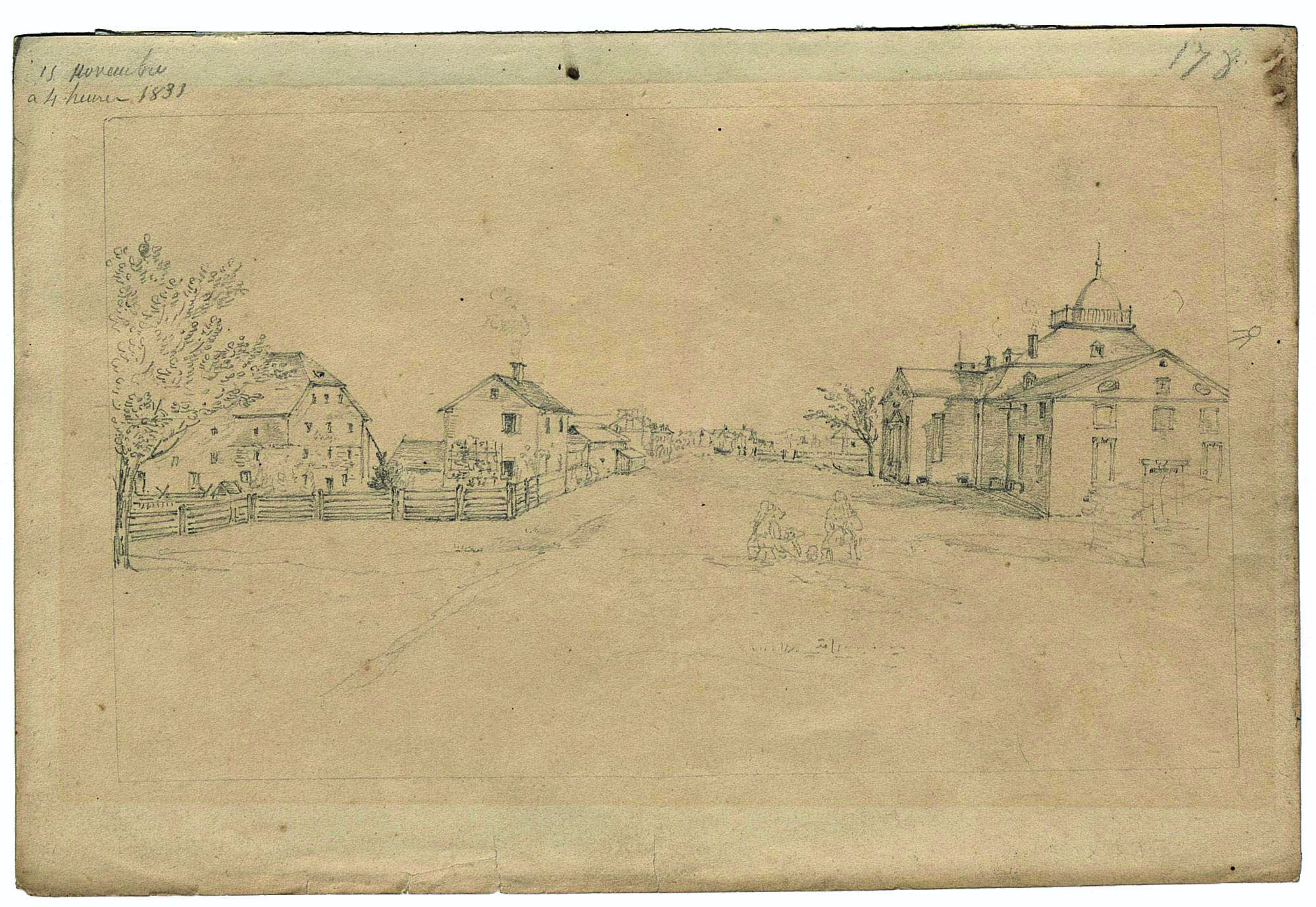

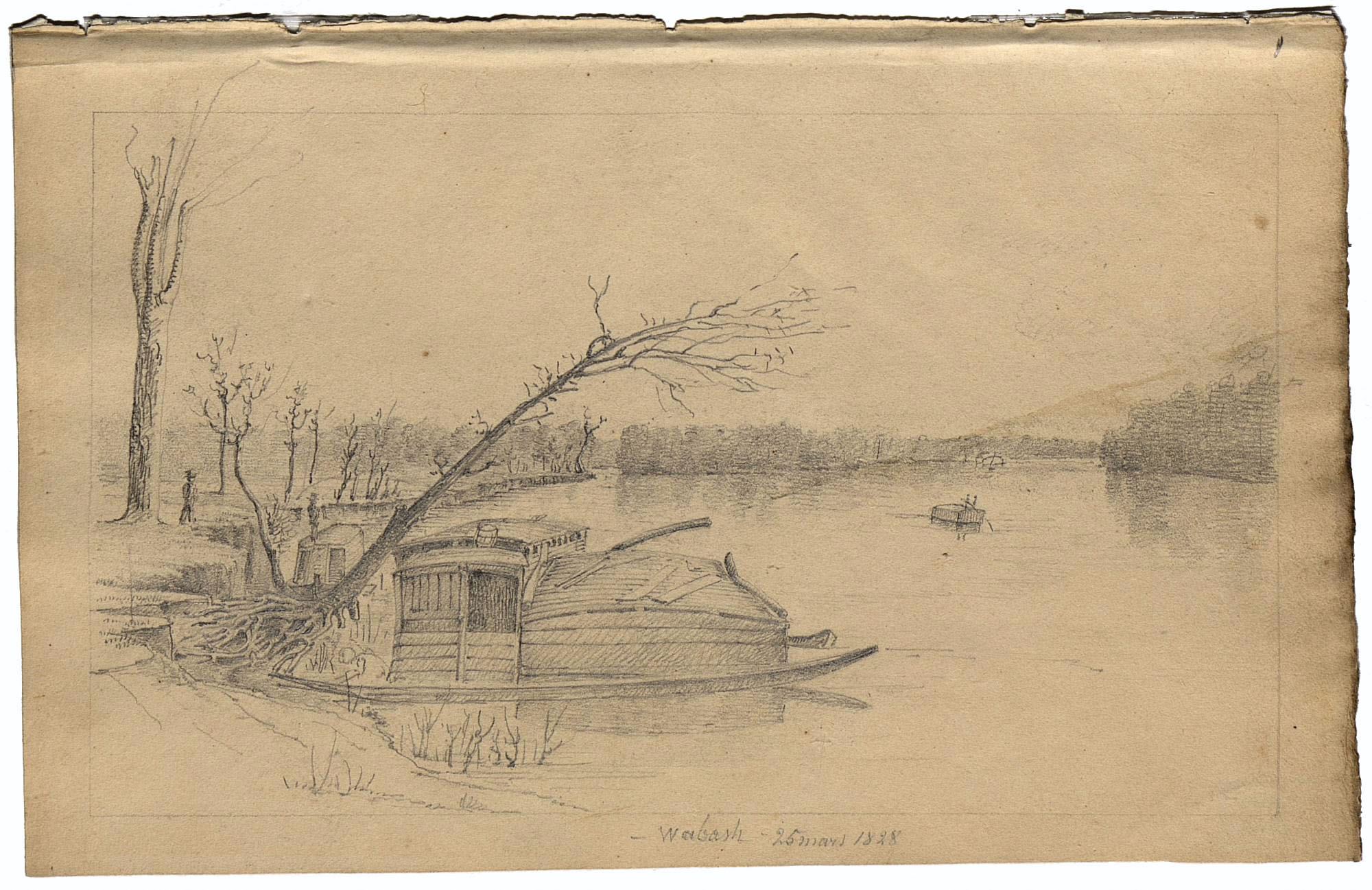

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur arrived at New Harmony

for the first time in January 1826. Approaching from the

southern hills and seeing a lush valley in the midst of thick

forest with the silver arms of the Wabash River cutting

through it, set against the backdrop of the wide prairies

of Illinois, he must have felt like Moses at the gates of the

Promised Land. In winter, of course, the site would not

have looked as magical, but in the spring's first strong suns,

with nature awakening and the fireflies lighting the earth like

stars in the sky, the traveler was transported to a new realm.

The forest and its animals - deer, beaver, bear, wolves, hares,

wild cats, squirrels and snakes - suddenly came alive. In theair and on the ground one could hear the calls of so many

birds: wild turkeys, parakeets, woodpeckers, nuthatches,

crested cardinals and chickadees. Abundant trees and vines

produced flowers and buds that decorated branch and soil:

gum trees, plane trees, cypress, apple trees, maples and thick

vines. Countless big trees, many taller than sixty-five feet and

wider than a yard, provided shade in all seasons: oak, beech,

ash and a great variety of nut trees. The richness of flora and

fauna filled Lesueur's heart with joy. Here was a paradisiacal

garden, an Eden in Indiana.

Back to Home Page

Boat landing of New Harmony, showing the Wabash and Cut-off Island

- by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1828)

Courtesy of the Natural History Museum in Le Havre