George Rapp's Harmonists and their Utopia in Indiana

Until the end of the eighteenth century, the region that

stretches from the Ohio to the northern Great Lakes was inhabited mainly by tribes of Algonquian Indians, the most significant being the Shawnee, Illinois and Miami. French explorers Jacques Marquette (1637-1675), Louis Jolliet (1645-1700) and René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle (1643-1687) were among the first Europeans to come into contact with these tribes in their home territory. After many voyages of discovery between 1673 and 1687, a growing number of trappers followed in their footsteps, enriching Quebec trading markets with furs and pelts of all kinds. As a result, toward 1731 François-Marie Bissot (better known as François Margane, lord of Vincennes, 1700-1736) commissioned a military fort to be built on the east bank of the Wabash.

A few years later, this fort became the center of the first

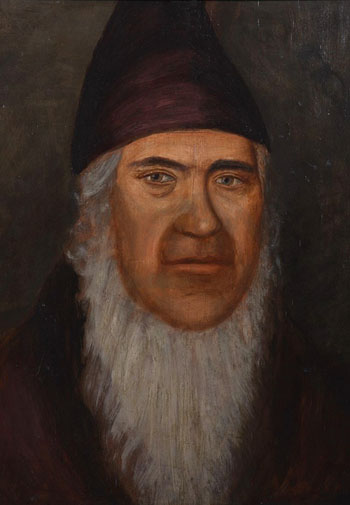

village of non-native Americans in Indiana. Under the directive of governor William Henry Harrison (1773-1841), future president of the United States, Vincennes became the official capital of the Indiana Territory from 1800 to 1813. Harrison put an end to the territorial aspirations of the native population by sending in troops to destroy their villages. He supervised the infamous Battle of Tippecanoe in November 1811 and two years later was responsible for the death of the last great Shawnee chief, Tecumseh (c. 1768-1813). It was during this time of war against Native Americans of the Indiana Territory that German spiritual leader George Rapp decided to build New Harmony. The Harmonists created their new community, starting in 1814, on the east bank of the Wabash River, fifty miles south of Vincennes and fifteen miles north of the confluence of the Wabash and Ohio Rivers. In 1825 Father Rapp sold the entire town to a utopian philosopher: the philanthropist and social reformer Robert Owen.

Back to Home Page