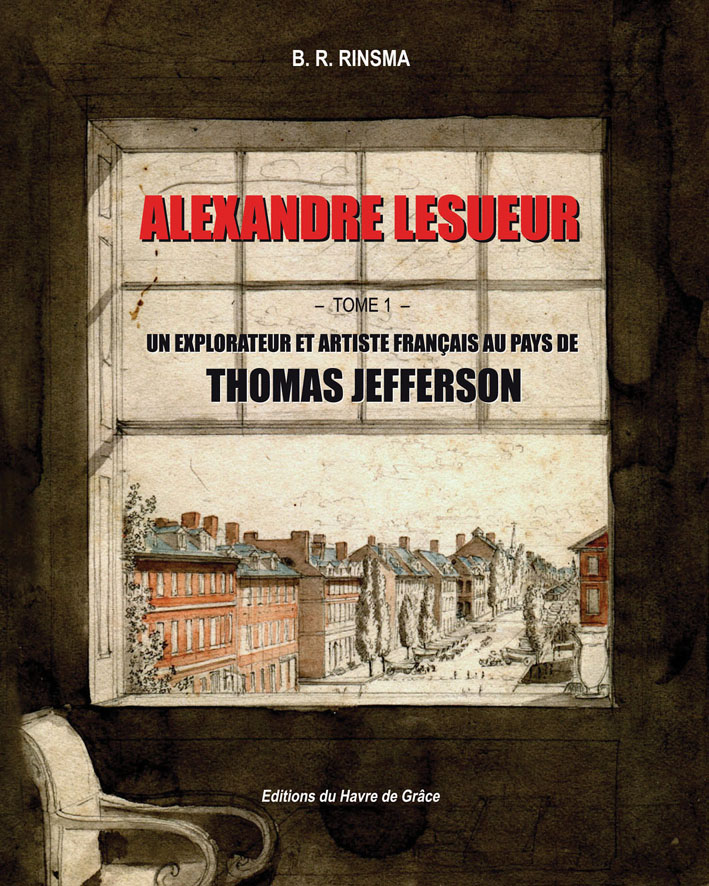

Maclure's Notes about Owen's Utopia

In his personal journal, during his visit of New Lanark, William Maclure noted enthusiastically how Robert Owen planned

to change his utopian ideas into reality:

"Mr. O[wen] proposes a new establishment of 700 acres in [a model of] agricultural improvement, [consisting] of a community of property, and every thing tending to dismiss the misery and increase the happiness of the human species. He starts on the broad principle, perhaps as new as it is true, that men's characters are not made by themselves, but in all circumstances and situations depend upon them, that is in habits, or in other words education. [He believes] that it is possible so to organize society as to drown the self in an Ocean of Sociability and make the interest of each the interest of the whole: harmonize society by combining their whole interest into one focus, like a burning lanse [sic: lens], increasing both the union and strength of the whole."

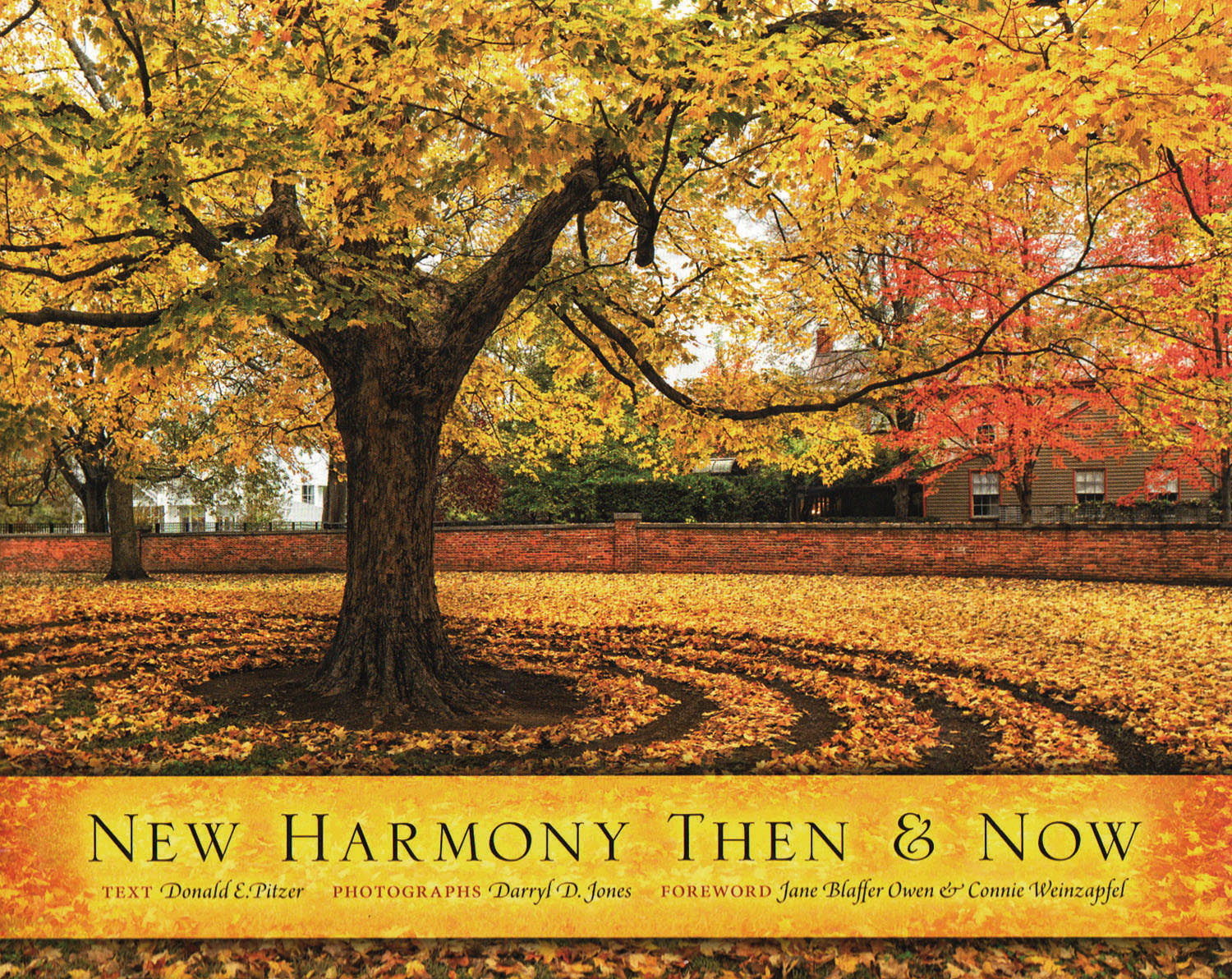

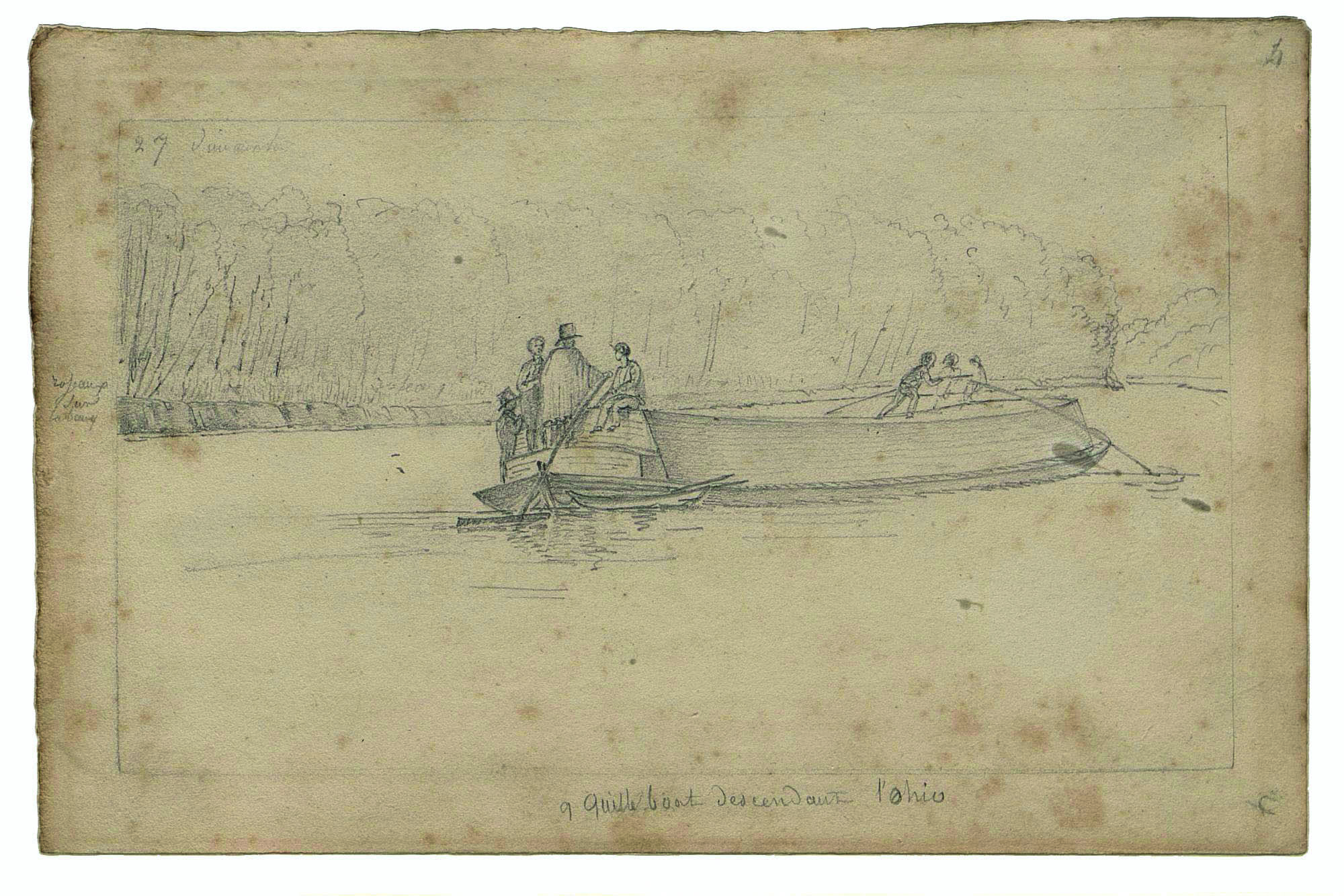

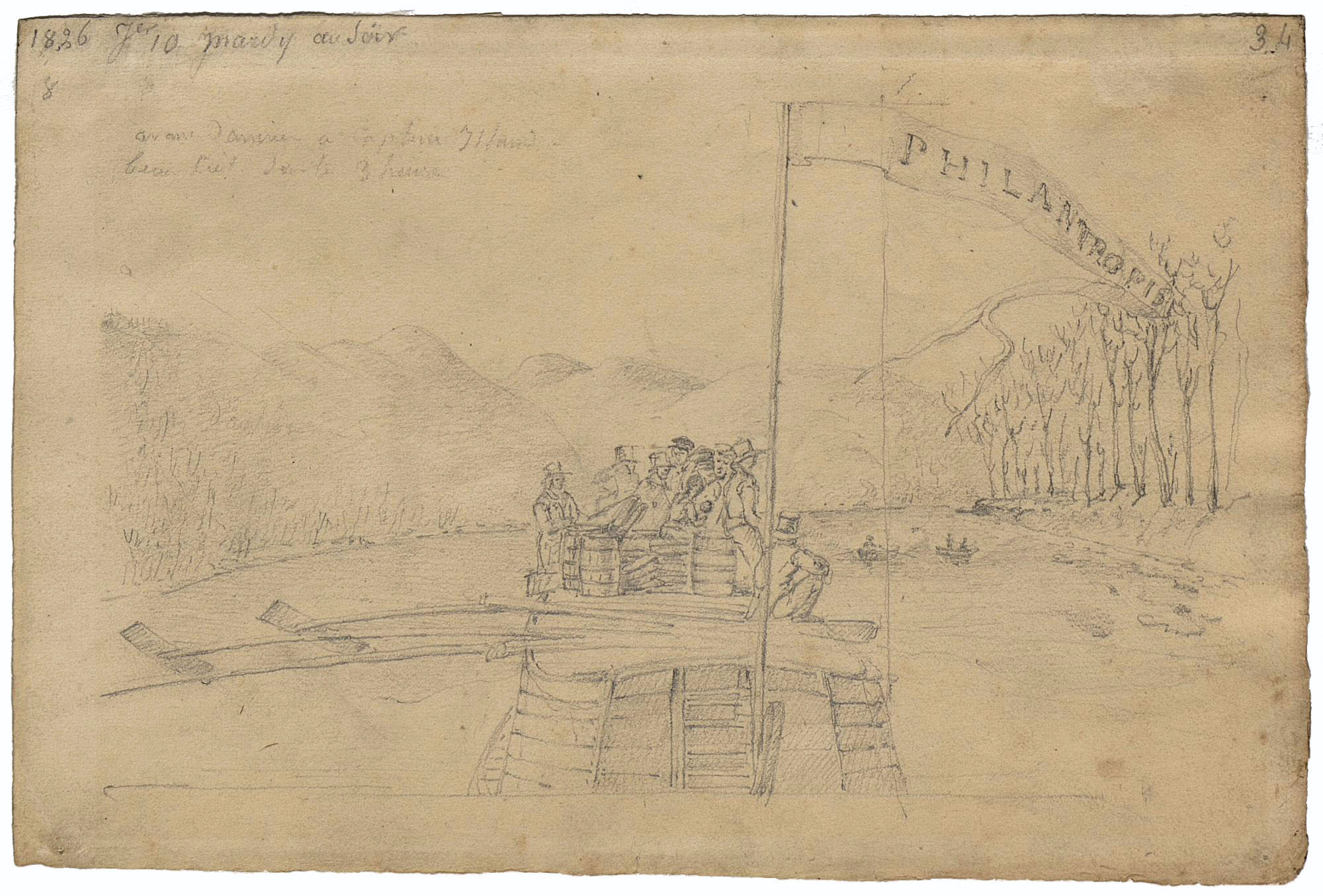

At the time of Maclure's writing, Owen had not yet bought New Harmony. To what "new establishment" did Maclure refer to? Was it the town in Indiana, since Owen may have already been told by George Rapp that he had put it up for sale? Or is it a reference to the Motherwell community near Glasgow, which, after several preparatory years, was still in the embryonic stage? Not far from there, the Orbiston community would be inaugurated in March

1825. Organized according to Owen's plan, it would last until the death of its founder Abram Combe in 1827. In that same year, a contingent of Orbiston members set sail for Ontario to establish the utopian colony of Maxwell.

The New Harmony community certainly became the most famous, but it was only one of many Owenite experiments. The last one would be Queenwood in Hampshire from 1839 to 1845. It is unclear which community Maclure had in

mind when writing his July 31, 1824, journal entry. On the other hand, it is quite evident that the American geologist was greatly impressed by the exploits of Robert Owen, whose fame had reached far beyond Great Britain.

Quoted from Rinsma, Eyewitness to Utopia, 139. |

|

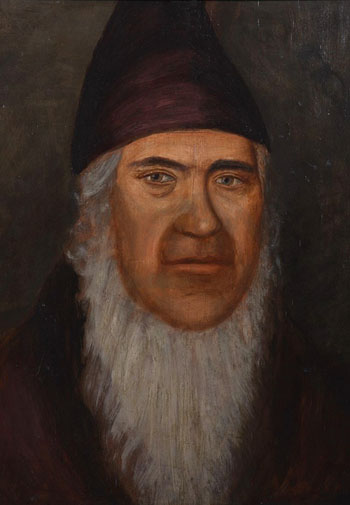

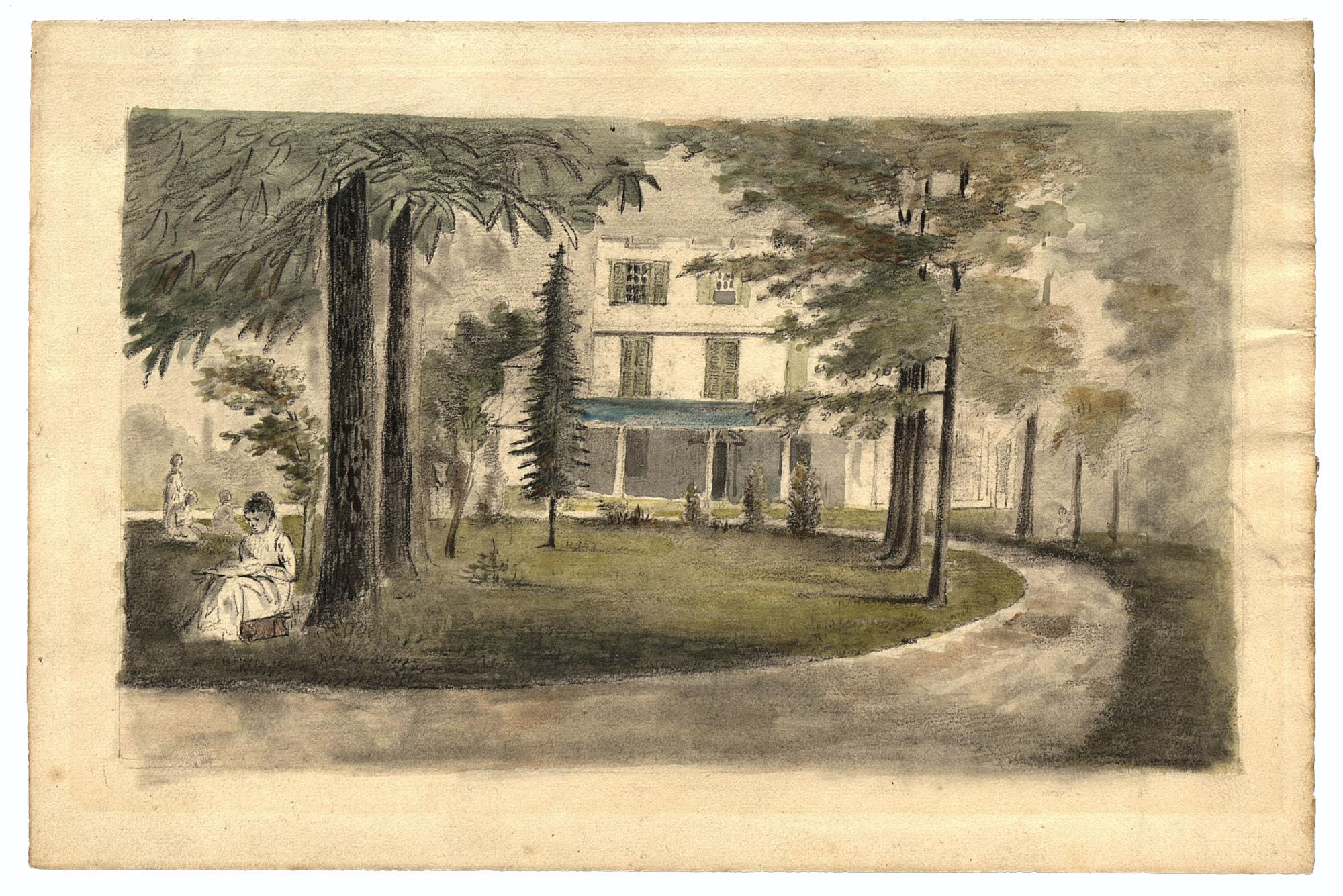

David Dale's New Lanark

After resigning from Peter Drinkwater's factory in 1795, Robert Owen became an associate in the Chorlton Twist Company. In July 1799 he and his financial partners bought David Dale's mills, creating the New Lanark Twist Company. Two months later Owen married Dale's daughter, Ann Caroline,

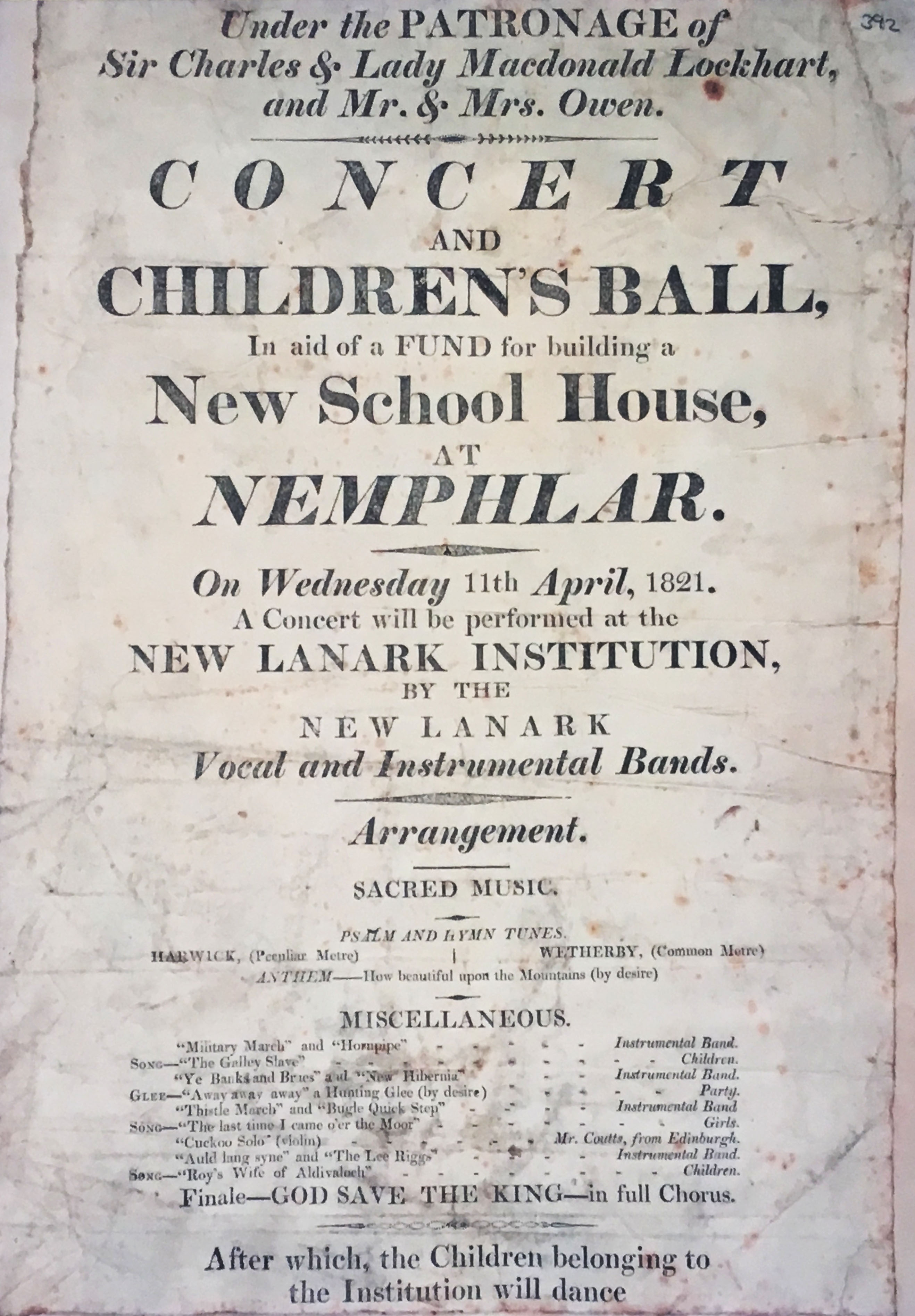

taking control of the New Lanark factory in January 1800. It had been in existence for fifteen years and was made up of four immense six-floor mills and many houses for workers. It employed 1,300 people to operate 12,000 spindles. The factory was modern, fitted with an ingenious hydraulic system, and heated by air conduits to diminish the risk of fire. Owen's father-in-law, the founder of the factory, had organized one-and-

a-half hour night classes where employees learned to read, write, dance and sing (the pupils were mostly orphans and poor people sent by the town authorities of Glasgow and Edinburgh). This was highly unusual for the era, to say nothing of the fact that Dale also provided social lodging for the workforce. When Owen took over, much of this was already in place. Like his son-in-law, Dale cared a lot about the wellbeing of his employees.

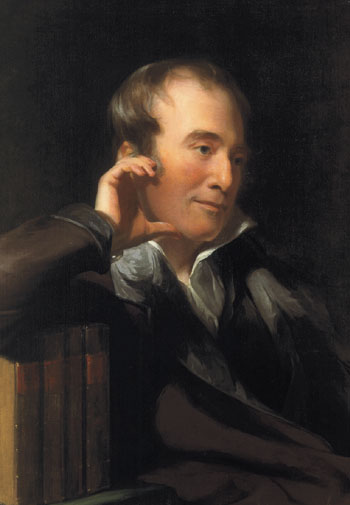

Robert Owen's Improvements

Working conditions could still be improved at New Lanark, however, and Owen began in earnest with a series of disciplinary measures. He also made many positive decisions to improve the lives of

his employees: he shortened work hours and stopped using children under ten, while establishing a free school for those above the age of five. Moreover, he opened a store where employees could buy all kinds of products 25% cheaper than elsewhere. The extra outlay of money did not deter Owen. In fact, his benevolence increased over time. He financed the school with profits from the store, adding a system of credit, which enabled his debt-ridden employees to buy food and other basic items. A newly created health insurance fund, supported by a sixtieth (1.7%) of salaries, took care of employees who were ill. When, in December 1807, Thomas Jefferson decided to prohibit the exportation of American products to Great Britain, Owen turned this action to his advantage. Although he had to close his mills because of supply problems, he continued to pay his employees who were without work. This greatly increased his popularity, and when the embargo was lifted, Owen could count on the devotion of all his personnel. |